This is part of the investigation series on women in migration, with special focus on the consequences of the International Law on Parental Child Abduction

Linh’s son was kidnapped from Norway to Lithuania in February 2017, whilst Kim had her sons relocated to Norway from South Africa through a Norwegian court order in 2018. Both are fighting battles that are crippling legally, not to mention the huge travel and living expenses in order to get their children returned back to them

For the personal safety of Linh and Kim, and their children, their real names are not used as they fear reprisal by their ex-partners.

“He says that the [Norwegian] government do not respect men here. They look at men like dogs,” said Linh who was recalling what her Lithuanian ex-husband said to her.

Linh was constantly subjected to psychological and physical abuse by her ex-husband. She was made to feel useless and had described the occasions where her ex-husband pushed her to the ground. When she asked for a divorce and wanted to just go home to Vietnam, her situation didn’t get any better.

UN has reported worldwide that thirty-five percent of all women and girls experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime, and half of the women killed worldwide were murdered by their partners or family.

That day, Linh was trying out a job, and came home to find both- her ex-husband and son missing. Initially, she thought they had gone to the supermarket. As the time passed to near midnight, she realised that something was terribly wrong.

Linh started calling her friends, who then told her to contact the police. She did. The police reassured her that it would be fine.

“I just couldn’t believe he would take our son back to Lithuania. And it was night time.”

Son Abducted by The Father

Linh was in shock. She thought that her ex-husband had found another place to live since he had said he would, in case they got separated.

“They told me not to worry and calm down since I was crying so much. So that time I did not tell them that my husband kidnapped my kid because I don’t want to believe that. Still, even now.”

The following day, there was still no sign of her son or husband. So, she went to the police station with her friend. There the police advised her to contact a lawyer.

“I waited until the morning, and went with my friend to the police to tell them that they still have not come back. Then I received a message from him. It was a picture. But he didn’t tell me where they were. I thought they could not go far. They must pass through Sweden, and through Latvia to get to Lithuania.”

It was believed that he was driving their son to Lithuania.

Linh had only stayed in Norway for a duration of seven months at that time. With a lack of understanding of the Norwegian language, she had to rely on her Vietnamese friends to help her find a lawyer. This did put her in a vulnerable situation, for example, she recalls that at least on one occasion, a so-called friend asked her for a sexual favour.

An application was made to Norway’s Ministry of Justice and Public Security to immediately return her son under the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Parental Child Abduction. The purpose of the convention was to protect children from the harmful effects of international abduction by a parent, by providing a legal procedure for the 98 countries who signed the convention.

Linh, scared, had to travel to Lithuania alone. There she had lost her court case regarding the return of her son back to Norway. Heartbroken Linh, appealed against the decision, only to lose the case again. The Lithuanian courts, while admitting that the actions of the father were unlawful, concluded they had to put the “best interest of the child” first.

“I cried very much of course, I still do, especially when you lose something like a child. Having tried my best already, I thought Norwegians could help me.”

Linh added, “Everyone [my friends] said that you will get your kid back because it is kidnapping, whether you have a job or not.”

Among her circle of friends, some told her to find a job because even if she does get her son back; she might face trouble with child protection services (Barnevernet).

“But I didn’t get back the kid anyway. Job for what? I cannot go back to Vietnam too because I am so sad, even though all I want to do is be there with my parents. They have only one kid who is me.” Linh decided to stay in Norway so that she could be geographically closer to her son.

The Lithuanian judges, in their deliberation, weighed Linh’s temporary resident permit in Norway against her son’s environment, where he is now attending a Lithuanian kindergarten with the assistance of his father’s family members. The judges therefore in the Lithuanian court arranged for her to see her son twice a month.

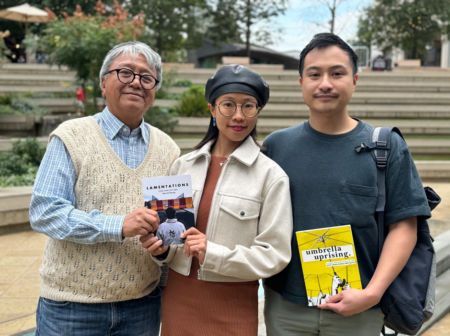

Continue reading after the photo.

A Common Language Lost Between Mother and Son

Being away from her son for so long and far away too, Linh has now lost a very basic connection with her son – a common language.

“I told my son [name omitted] mom don’t understand you. But he is sweet, he said viskas gerai which means it’s okay in Lithuanian.”

Linh continued to weep intermittently during our interview and tried to fight back her tears.

“It’s so hard; it’s unimaginable. I think about the court time, I think about now. It’s heartbreaking and so tough; I love my kid so much.”

There is a wealth of research showing that children who have been abducted show feelings of confusion, loss, and grief for the left-behind parent, and a corrosion of ability to trust.

In a European Union study, researchers noted that “children who did not return are more likely to develop emotional and behavioural problems when abducted by a parent who was not their primary caregiver and when they were not informed about the abduction.”