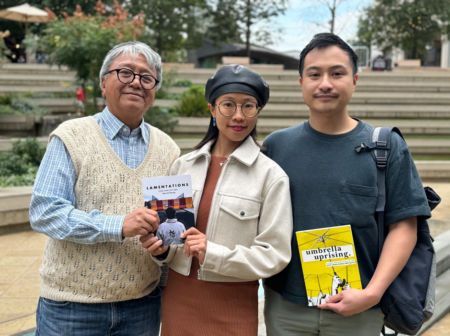

Ryan D’Souza guiding visitors at the Nobody’s Listening exhibition in Oslo. Photo: Ka Man Mak

From November 13 to 24, a section of Oslo’s Nobel Peace Center was transformed into a gateway to northern Iraq, bringing visitors face-to-face with the harrowing reality of the Yazidi genocide. The Nobody’s Listening exhibition showcased an innovative blend of virtual reality (VR), art, and survivor testimonies to commemorate the Yazidi genocide by ISIS, marking its 10th anniversary. Though, it was more than just an exhibition — it was a visceral call to action.

Curated by Ryan D’Souza, the experience made audiences walk in the shoes of survivors like 25-year-old Thikran Mato, who spoke openly about his ordeal. The VR and artwork provided both an education and a deeper understanding of this difficult chapter of history.

Remembering Sinjar: The Genocide

In August 2014, the Islamic State (ISIS) stormed Sinjar, home to the Yazidi minority in Iraq. They sought to erase this ancient, mostly Kurdish-speaking ethnoreligious community through mass killings, abductions, and sexual slavery. Men and older boys were executed; women and young girls were enslaved and subjected to institutionalised rape. Over 5,000 Yazidis were killed, and approximately 3,000 remain missing. Young boys, forcibly separated from their families, were trained as soldiers, indoctrinated with ISIS ideology, and coerced into killing, often under threat of death themselves.

Thikran Mato was just 15 when ISIS attacked his village, Kocho. “The chaos, fear, and sound of gunfire—those memories never fade,” he recalls. “I remember mothers holding their children tightly and people trying to protect each other.” This was also the last time Mato saw his father, “He smiled at me before he was taken away.”

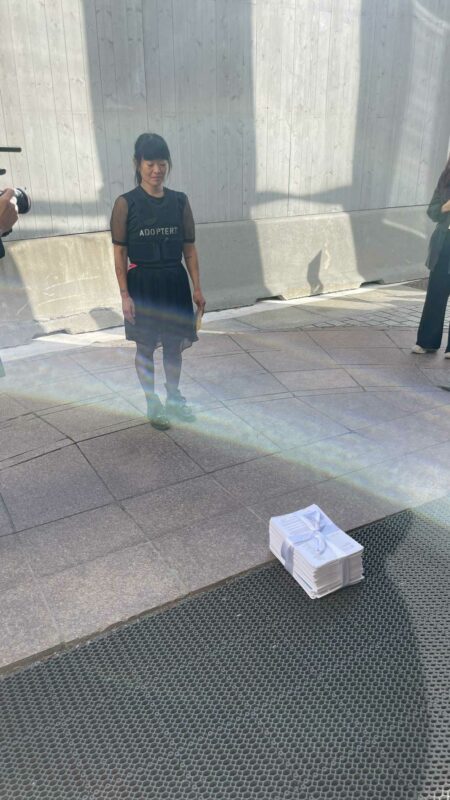

Thikran Mato and his mother in Germany. Photo: Newsha Tavakolian/Magnum Photos, photographed by Ka Man Mak

Forced into captivity, Mato endured two years of indoctrination, clinging to hope. “I drew strength from my faith, memories of my loved ones, and the belief that I needed to survive to share our story with the world.” Many Yazidis escaped by fleeing to Mount Sinjar, enduring starvation and dehydration in harrowing conditions, while others were eventually rescued and resettled in countries like Germany, which has welcomed survivors to provide safety and rehabilitation.

Healing and Rebuilding After Trauma

Today, while Mato has rebuilt parts of his life in Germany, the trauma persists. “The memories are overwhelming,” he says. Even the sound of helicopters — a universal symbol of rescue — evokes panic for him, reminding him of moments of helplessness. Dealing with trauma while adjusting to a new reality is incredibly challenging for Mato and many Yazidis.

“Finding safety, rebuilding trust, and coping with the loss of loved ones were the hardest parts,” he explains. “For example, many Yazidis, including myself, find it difficult to trust people in positions of authority, like police or officials. It’s because of past betrayals by those who were supposed to protect us.” Despite this, he channels his pain into advocacy, determined to ensure that the world does not forget what his community endured.

Experiencing the Past in VR

The Nobody’s Listening exhibition aims to remind the world what has happened, and bridge the emotional and educational gap through technology. The 12-minute VR experience plunges visitors into the heart of Sinjar, from peaceful Yazidi villages to the moment ISIS attacked. The visuals are stark: burning homes, screaming families, and, later, the resilience of a community fighting to rebuild.

A visitor experiencing the VR firsthand. Photo: Ryan D’Souza

Ryan D’Souza, the exhibition’s curator, explains why VR was chosen, “I feel we’re living in an era where people are desensitised to atrocities, and suffer from short attention spans and a lack of empathy. VR transports viewers into someone else’s reality—it’s as close as you can get to standing in their shoes.”

D’Souza, who has spent the past ten years working on human rights advocacy and genocide prevention, emphasises the unique power of VR. “We have seen students saying they learnt more about the Yazidi genocide from the VR experience than their textbooks. Arranging discussions between visitors and genocide survivors helps too, it leaves an indelible mark,” he says. One European foreign minister, after experiencing the VR, even traveled to Iraq to meet survivors.

The response in Oslo mirrored these successes. “We had visitors from all over—Kazakhstan, China, Germany,” says Andreas, an employee at the Nobel Peace Center. “Some people didn’t even know about the genocide. Others cried after the experience. It’s powerful.”

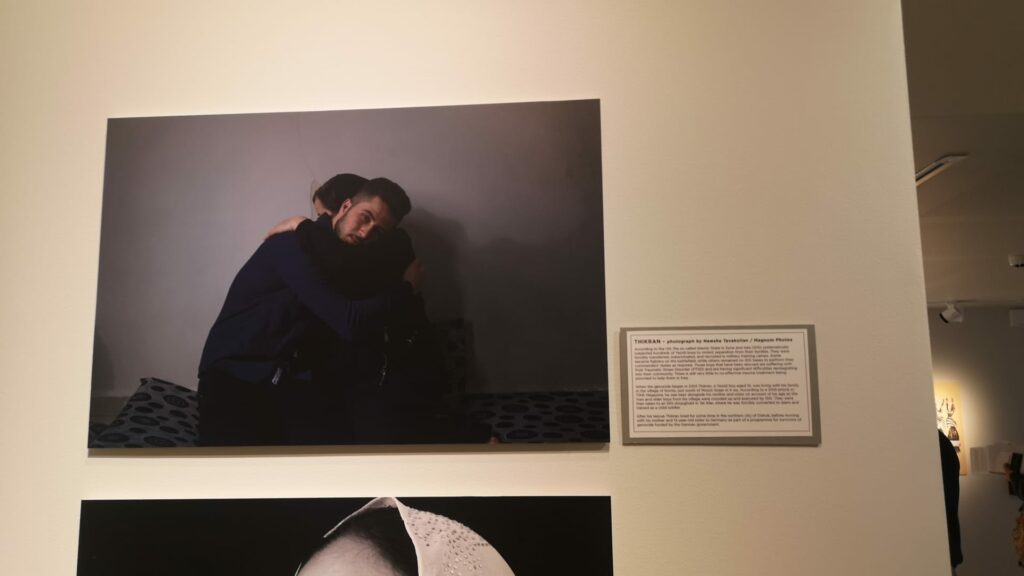

While the VR was the exhibition’s centerpiece, the surrounding art amplified its message. Paintings and photography displayed the depth of the Yazidi community’s suffering and resilience. D’Souza noted, “The VR is only 12 minutes. The artwork provides a broader platform for survivors and other communities affected by ISIS, like Shia Turkmens and Sunni Arabs, to tell their stories.”

The exhibition includes art work by all communities affected by ISIS. Photo: Ka Man Mak

Action Beyond Awareness

For survivors like Mato, sharing their story is a double-edged sword—painful yet empowering. “It’s hard to relive the past, but knowing my story can inspire change gives me purpose,” he says. Through exhibitions like this, he hopes to educate global audiences and push for justice.

When asked what justice looks like, Mato is clear: recognition, accountability, and rebuilding. Thanks to the remarkable advocacy by Nadia Murad and other Yazidi survivors, as well as local and international human rights organisations, “historic action” was taken, according to D’Souza. “This includes the establishment of UNITAD—a UN team with mandate to investigate the genocide, recognition of the genocide by various governments, and funding to help the Yazidi community.” However, he warns: “Quite simply, this is not enough given the needs and challenges still facing the community, as well as backsliding by governments regarding the threat posed by ISIS. More must be done to counter hate speech against the Yazidis and to support all ethnoreligious communities in Iraq.”

Mato agrees, “Awareness is growing, but action often falls short. Leaders must prioritise justice and long-term support for survivors. We also need to focus on education and show the world what happened to us to prevent history from repeating itself.”

D’Souza expresses optimism about Norway’s role in supporting the Yazidi cause. “Countries like Norway can lead the way in recognising the genocide and funding survivor support initiatives,” he says. Mato adds, “I hope Norway continues to be a voice for justice and recognition.”

The VR experience has already impacted policymaking. In Iraq, it has been integrated into genocide commemoration activities, and plans are underway to include it in school curricula.

A Path Forward

As the exhibition wrapped up in Oslo, its impact lingers. Visitors left with a deeper understanding of the Yazidi genocide and a sense of urgency to act.

D’Souza will take the Nobody’s Listening exhibition to the United States, Canada, and beyond. For individuals moved by the exhibition, both D’Souza and Mato have simple advice: speak up, support local charity organisations like Yazda, and advocate for justice. “At a minimum, share what you’ve learned with friends and family,” says D’Souza. He is delighted that many visitors at the Nobel Peace Center bought Nadia Murad’s book straight after watching the VR. “At a deeper level I hope this means that they speak to those people they know in influential positions in government and elsewhere to help the Yazidis and others who are suffering today,” D’Souza says.

In an era where tragedies are often reduced to fleeting headlines, Nobody’s Listening forces us to confront the human cost of inaction. As Mato poignantly put it, “Ten years later, the world still has a choice—to forget, or to stand with us.”